I went to watch the much-lauded Anthony Minghella production of this Puccini favourite the other day, my 4th opera in as many months and perhaps interestingly in as many countries. My new found interest in this art form began when I went to watch a modern small scale production of La Boheme in Copenhagen, directed by an old friend Amy Lane. That remains my favourite of the 4 shows I have seen so far. Since then I have watched from the cheap seats, two big lavish productions: La Traviata at the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm and Falstaff at the Berlin Staatsoper and the third, the subject of this article, Madame Butterfly at the English National Opera in a far from cheap seat (though subsidised in the form of a cast discount) in row D of the stalls. I realised, incidentally, sitting there in my privileged position, that I actually prefer being able to see the orchestra and therefore the best seat in the house for me is probably in the front of the circle.

As a European opera production newbie I have noticed a few things that more experienced goers might take for granted, which I think worth noting before I myself start to accept them as normal without thinking:

- Bizarre swampings of the stage in the final act with 50+ actors/extras, who have hitherto not been seen, in what appears to be a simple show of extravagance with no artistic merit or need. This happened in both La Traviata and Falstaff, completely different productions in completely different cities. What is this all about? In Falstaff in particular, I felt embarrassed for those performers. They had no idea why they were there or what they were doing and the sexualised goings-on in the Bacchanalian fantasy sequence in the final act were excruciating.

- The acting is different (hardly a revelation, I suppose) and takes a massive backseat to the demands and rigours of singing. This is fine with me, but it takes an adjustment if you are used to watching actors trying to be as realistic as possible (to the extent that you can’t often hear them nowadays). It is a similar adjustment one makes when you go to watch a panto, I think. After a short while it is easy to accept the new style of acting but it is worth pointing out that it could easily be better, especially for the extras or supernumeraries as they are called, with an acting workshop getting them to think about what their characters want.

- There are a lot of snobs who go to the opera simply for the sake of watching others and to be seen. This is part of society, I realise, but it is quite tedious. In theatre, there is always someone who will laugh loudly at a 400-year-old “joke” in a Shakespeare play, thereby telling himself and others in the audience and the actors on stage that he is really clever and cultured and gets it. This same person, I have noticed, will fail to laugh at anything else the production may have added, perhaps for a contemporary-based laugh, which the rest of the common audience will get. These pompous self-inflated egotists are outnumbered in UK theatre audiences nowadays, thankfully. These people are snobs, and my point is they appear to go en masse to the opera in Europe. The disdain with which I was looked at for showing up with a ticket dressed in my travelling gear of puffa jacket and walking boots was apparent. I may be wrong, but they seemed to have less appreciation of the actual show than I did. In any event I was delighted to stomp around, bagging myself a rare table in the interval, annoying these people.

- Staging. It is as if the highly revered directors of these productions have forgotten that there are cheap seats that can not view the entire stage! Move the action about the stage! This is the very least you have to do, surely?! The ENO doesn’t suffer from restricted views as much as the other auditoria I have recently visited, not least because there are no columns supporting the structure. I have watched a few shows in the theatre, especially the Royal Court recently, from restricted view seats and the same criticism could be levelled there too.

- It is taken for granted that the singers sing it flawlessly and the orchestra is note-perfect throughout. This is a pretty high bar! Which they always seem to achieve. That is quite incredible and the thing I love is that it sounds more or less exactly as it did when it was first heard, without amplification. It is this point which probably is the main reason for the existential problems I am about to address. What is the point of Opera today? To get it sounding right and reflect the time it was written or to update things and make it relevant?

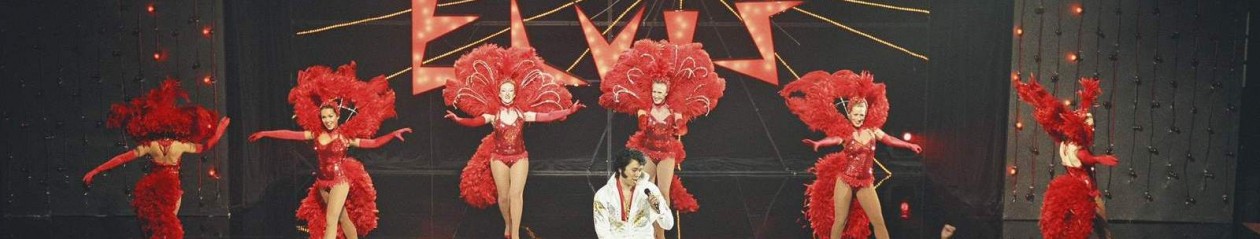

The production of Madame Butterfly at the Colosseum is in its 16th year and is stunning. I was struck by how simple and effective the set and production were, compared to the two other grand operas, and how effectively the story was told. I also found the acting, particularly by the actor Roderick Williams, who played Sharpless, the US Consul, to be better than the usual. I appreciated a moment when he made as if he had something to say when it was someone else’s line, and he held his tongue. Why others don’t try this simple but effective technique is a mystery. I suspect it is because they have not really thought of their Stanislavskian “scene objective” and don’t really know what it is they might say at that particular moment. The Japanese scene shifters, aka kuroko, were so precise that they all appeared in view always at the precisely same moment, a feat that having watched theatre for decades I know is almost impossible! I enjoyed the use of red ribbons for blood, this theatrical device being as effective as it was over 70 years after Laurence Olivier’s production of Titus Andronicus had Vivienne Leigh spew them as Lavinia and I found the doll of Cio Cio San’s young son, worked by three puppeteers, very moving. Given the nature of the musical bar being set so high I almost took for granted the singing of the cast, but it should be mentioned that they were all great.

It was the best of all 3 major productions by far in terms of design, direction and story (though I preferred the small scale La Boheme to all of them).

I was driven to write this because it is the story of Madame Butterfly and production as a whole that left me with things to contemplate, about which I am uneasy.

Casting. Historically, casting white actors as Japanese is something that has happened in probably every single major production of this opera since it was written. This production offers up the argument in the programme: “An insistence that only Japanese sopranos sing the role of Butterfly would deny us the chance to hear many fabulous interpreters of the role. Moreover, adopting a policy of strict literalism actively works against the long-fought-for policy of colour-blind casting, for surely if Butterfly must be Japanese, then Tosca must {italics, sic} be white Italian (though not all would agree). This is a conundrum that is unlikely to go away.” Anyone who has tried to argue the merits of inclusive casting, as I have for over a decade within Equity – and much longer outside of that conflicted and confused trade union – will recognise the above as argument 1.01. This is not the place to re-state old rebuttals, but it is worth pointing out that theatre in UK faced this issue and argument (which is all to do with white privilege) 30+ years ago. Easier here to ask, if the ENO’s argument is correct then why has not a single white actor played Othello for the last 30 years? The “World of Opera” exists in a bubble that by its own self-definition, performs works without changing a note, that sounds exactly as it would have when it was composed. The argument that this fundamental would be compromised was made when I was a kid by white people about Shakespeare. Maybe someone should challenge this fundamental.

Story. Maybe it is because I was in Miss Saigon, which is based loosely on Madam Butterfly, for over 600 shows, but I don’t buy the romanticism. I am very much of the opinion that if you were to flip the ethnicities of the Asian romantic heroine, the story would be different. I made that very point in a sketch satire that I wrote for tv once. Here is the relevant bit (broadcast on C4 in 2005)

Paul Chan (explaining the plot of the popular musical): This GI falls in love with a beautiful Vietnamese girl and knocks her up. And when the war is over, he goes back to the States and forgets about her. But the thing is, the baby gets born so she tries to find this GI…

Me: In the States?

PC: Wherever. And basically, because he’s married to another woman, she tops herself. That’s it.

Me: Sounds alright.

PC: Yeah. Its brilliant. It’s very romantic.

Me: But why does she top herself?

PC: Because she’s in love with him. It’s a beautiful story. Forget it.

Me: That’s not romantic.

PC: Eh?

Me: Look at it this way. If a Chinese geezer came over here and knocked up a beautiful girl like (thinks)… Carol Smilie..

PC: Carol Smilie?

Me: OK, then … (thinks) Errr.. Jordan.

PC: OK. Go on.

Me: If he went back to China, married someone else and Jordan has his baby and then she topped herself because she was still in love with him, people would say, “It’s a joke”!

PC: So what are you saying?

Me: It is because she’s East Asian! Miss Saigon is East Asian, that’s what makes it a romantic story. If she were Jordan it would be stupid.

PC: But she isn’t Jordan.

Me: That’s what I am saying.

PC: And it isn’t stupid, its romantic!

It is because she’s East Asian!

For me, Cio Cio San, the 15-year-old Madame Butterfly in Puccini’s opera on whom Miss Saigon is loosely based, suffers from the same oriental fetishism by its audience and book author as Kim in the popular musical. This “exquisite tragedy” is, in fact, a frustrating depiction of a naïve girl’s self-inflicted ordeal ending with an inevitably noble suicide, told from the viewpoint of white superiority and imperialism. It is eyebrow-raising to observe the fact she is 15 in today’s climate. The fact is in today’s tabloid culture, Pinkerton, Butterfly’s “GI” in this Miss Saigon reverse analogy, is a child-abusing paedo, who evilly sets out from the very start of the play his plan to abuse his temporary Japanese wife and abandon her like a property with a short notice lease, which is exactly what happens (not unlike Gary Glitter did, it is worth pointing out).

It depends what you want from your Opera, I suppose. The programme acknowledges that there are problematic themes with the piece, namely orientalism, misogyny and casting (all of which I agree with). There is no mention of paedophilia/Gary Glitter, or that the under-agedness makes it undeniably sordid as well. Despite it being a fantastic production, I can’t ignore any of these issues. And the question of whether these issues can be addressed is actually the same fundamental question of whether Opera itself can reform and make itself relevant to a new generation. The question for Opera becomes whether its inability to move with the times will spell the end for the whole art form – or whether on the contrary it will flourish as people like to get away from the new 21st century hubbub of digital unsocial media etc.

I expect the Opera world to forever reside in a past that does not exist any more, and hoping that by acknowledging the problems intellectually they will get away with not having to actually address them. The kind of past that Remainers mock Brexiteers for still believing in, but a majority still want. A time when you could say that Jimmy Savile may have been a bit creepy but at least he raised a lot of money for charity.